Gamification

Gamification

Introduction

This chapter is based on a webinar prepared in the scope of the DE-TEL project and that was later offered as a 2-part workshop at the JTEL Summer School 2022 in Greece. We reflected a lot about possible changes to the structure and objectives of this resource. After careful consideration we decided to maintain the workshop structure as we believe that its overall objectives can be far more useful for PhD candidates than a more theoretical-driven approach. Hence, this chapter begins with a soft introduction to concepts closely related to gamification, such as its differences to game-based learning and serious games, most well-known gamification frameworks and most common users/players typologies. In the second part we propose a workshop activity that pretends to guide readers through a process of designing a gamification-based research plan. For that we make available a use case (Meet Helen!) that will situate readers in a research context that implies decisions regarding the evaluation of a gamification strategy, the research methods that could/should be applied to the situation and the design of a research plan for this specific use case.

Conceptual overview

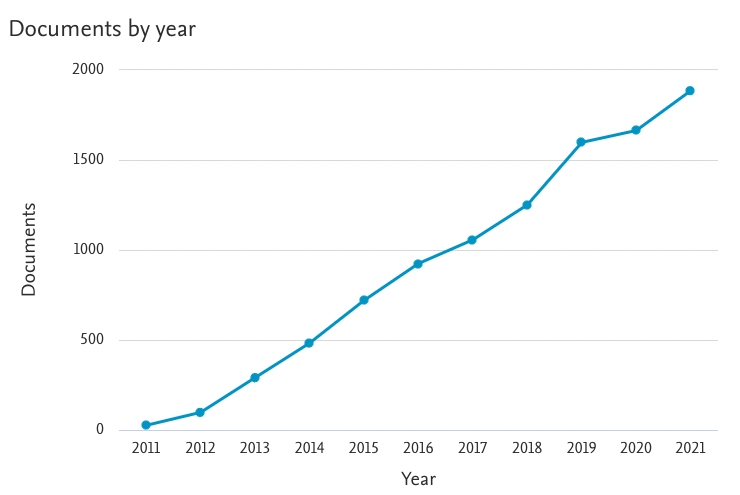

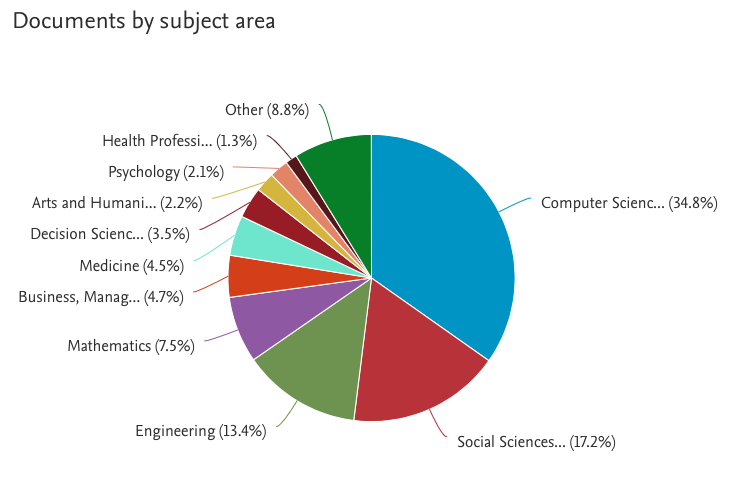

The gamification concept has gained, in the past ten to fifteen years, a major relevance in the technology field. This rising relevance can be attributed to several factors. One of those factors is related to the increasing time we spend using apps or web services that, in turn, try to engage and retain its users for as much time as possible as this is paramount to their business models. For that they typically resort and explore basic human features such as pleasure and reward, features that are also the human features that are most explored in traditional and digital games. The “use of game design elements in non-game contexts” (“From Game Design Elements to Gamefulness: Defining Gamification.,” 2011) is the most well-known definition of gamification and encapsulates this strategy of applying and integrating these elements, commonly used in games, in other contexts. A quick survey of the SCOPUS scientific database shows us that the use of the term ‘gamification’ has been steadily increasing since 2011, particularly in the computer science and in the social sciences fields.

These two areas are, of course, the foundational areas of the Technology-Enhanced Learning field. Several authors claim that the use of gamification elements and strategies in education can enhance learning as pleasure and reward typically activate important human functions such as attention, motivation and memory (“Defining Gamification: a Service Marketing Perspective.,” 2012).

It is important, at this stage, to clarify some differences between gamification and other terms that are frequently but mistakenly used in an interchangeable way.

One of those terms is the term game-based learning. According to Qian and Clark (“Game-Based Learning and 21st Century Skills: A Review of Recent Research.,” 2016), “game-based learning describes an environment where game content and game play enhance knowledge and skills acquisition, and where game activities involve problem solving spaces and challenges that provide players/learners with a sense of achievement”.

The other term is, of course, the term serious games. Serious games are computer-based games with a primary purpose other than entertainment, ranging from anywhere between advertisements to military training exercises (Serious Games: Games That Educate, Train, and Inform. , 2006)}.

In other words, game-based learning can be defined as the use of (existing) games to enhance learning, serious games are custom made games for specific learning purposes and gamification encompasses the application and integration of elements of games into non-gaming (learning, for instance) contexts. There is a very interesting and thorough discussion regarding the effectiveness of the use of games and game-based learning approaches. As (“Our Princess Is in Another Castle: A Review of Trends in Serious Gaming for Education.,” 2012) claim “to date, there is limited evidence to suggest how educational games can be used to solve the problems inherent in the structure of traditional K–12 schooling and academia. Indeed, if you are looking for data to support that argument, then we are sorry, but your princess is in another castle”. The results regarding the effectiveness of using gamification in educational contexts are also mixed. In an extensive literature review, (“Does Gamification Work? A Literature Review of Empirical Studies on Gamification.,” 2014) report that “gamification provides positive effects, however, the effects are greatly dependent on the context in which the gamification is being implemented, as well as on the users using it”.

This discussion regarding the importance of the context and the users is paramount. Some authors stress that, in order to be effective, gamification experiences should focus on the the process of making activities more game-like (Werbach, 2014) and on practices that elicit user experiences typical of games (“How Gamification Motivates: An Experimental Study of the Effects of Specific Game Design Elements on Psychological Need Satisfaction.,” 2017). That is to say that although gamification implementations may vary, they typically share a lot of common elements that are very important in terms of its final results. These are its mechanics, experience design, engagement strategies, and of course, the users/players. More on this can be found in detailed analysis of gamification frameworks such as the MDA framework (“MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research.,” 2004) and on other approaches such as the hierarchy of game elements developed by Werbach and Hunter (For the Win: How Game Thinking Can Revolutionize Your Business., 2012).

Regarding the users/players, it is important to take into account several approaches that aim to categorize players such as the ones developed by Bartle (Bartle, 1996) and more recently by Marczewski (Marczewski, 2015). In the next sections we will tackle this issue by presenting a specific use case as a context for the implementation of a gamified approach to learning. We will then discuss how to research this context in order to collect data to validate the effectiveness of the strategies used.